At the Nesta Government Innovation Summit last September, Geoff Mulgan, chief executive at Nesta, made a surprising declaration. In the midst of an unprecedented political crisis, he announced “a golden age for local government”. Local government, he argued, has more freedom than ever to experiment with new solutions and is the level on which to rebuild citizens’ eroding trust in government.

Whilst the idea of reinforcing local governments isn’t new, it has somewhat lost steam in recent years. Legislation that reinforced local councils’ prerogatives generated high hopes in the early 2010s, but led to disappointment as it failed to truly empower councils and to reconnect citizens with their local governments. So, could it be that renewed localism is really the answer to the UK’s recent political turmoil?

Localism in the UK, a complicated love story

Localism, and the idea that government should be in part decentralised, is an idea that has been around pretty much since the central government itself was created. Devolution is seen by many as a way to boost innovation in local councils, increase efficiency and improve trust levels. The positive impacts of devolution have been observed in Scotland, Wales or in the Greater London Authority where local governments with increased prerogatives have seen improved service delivery and better dialogue with citizens.

In 2011, the government passed the Localism Act in the hopes of replicating these successes on a larger scale. Ron Clark, MP for Decentralisation, justified the need for the act in the following terms:

“For too long, central government has hoarded and concentrated power. Trying to improve people’s lives by imposing decisions, setting targets and demanding inspections from Whitehall simply doesn’t work. (…) It leaves no room for adaptation to reflect local circumstances or innovation to deliver services more effectively and at lower cost. And it leaves people feeling ‘done to’ and imposed upon – the very opposite of the sense of participation and involvement on which a healthy democracy thrives.”

The act was designed to increase local councils’ prerogatives on pressing issues such as health, education or housing, giving them room to innovate and improve services by relying on local knowledge. Part of the act’s aim was also to give communities a sense of empowerment by reconnecting citizens with the decision-making process and creating frameworks for local referendums.

Despite these great promises, the enthusiasm that accompanied the announcement of the Localism Act quickly faded away. Two years after the Act came in effect, Jules Pipe, mayor of Hackney, said that “the Localism Act has had little effect on the balance of power between local communities and Whitehall, or on the balance of power between central and local government.” In short, despite the Act’s good intentions, it had failed to make any real difference. Results were still lacking, power had remained too centralised, and funds were too low to truly allow councils to innovate and tackle new challenges.

In 2016, the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act was introduced in an effort to push localism further. The legislation further enshrined cities and local governments’ rights to manage housing, transport, planning and policing policies and allowed for the introduction of elected mayors. Despite these changes, skepticism regarding the effects of localism remained.

So, why now?

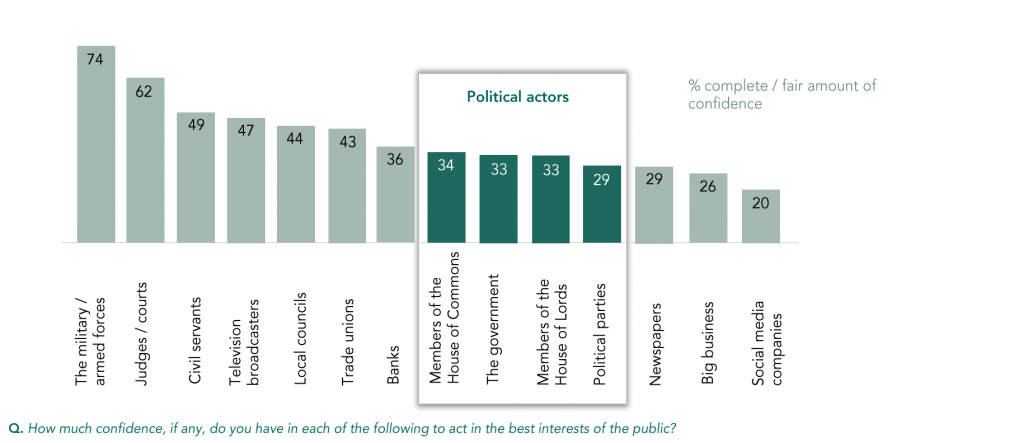

There seems to be a general consensus that something in the UK’s political system is broken. A recent Hansard Society study shows that distrust in the government is at its highest point in 15 years – keeping in mind that such data wasn’t collected before then. Confidence in MPs has dropped significantly, satisfaction with the political system is at al all-time low, and most citizens don’t trust the government to act in their best interest. 72% of respondents to the study said the system of governing needed “quite a lot” or “a great deal” of improvement. The prevailing feeling is that citizens have “lost control”: 47% feel they have no influence over decision-making, a feeling which in turn fuels distrust and disengagement from the country’s political life. In this context, what can localism do?

First of all, local councils are the best placed to rebuild dialogue. The same studies which show the fast erosion of trust also show that local institutions and representatives remain more trusted. Citizens are more likely to want to engage on a local level – making local councils the best placed to build trust and encourage civic engagement initiatives. When asked who they felt had their best interest at heart, 22% of respondents to the Hansard Society Study cited “political parties”, 33% cited the government and 44% cited the local government. 57% of citizens also agree that “decisions about public services are better if made locally”.

“When we asked recently who has the public’s best interests at heart for The Hansard Society, 44% say local government does, compared to only 33% for the government, and only 29% for political parties.”

Hansard Society Study, 2019

According to the 2019 Councils Can report, citizen dialogue is at the heart of the council’s duties: “The three most important roles that councillors see themselves taking on are representing residents, supporting local communities and listening to the views of local people.”

Secondly, at a time when the national government is focused on international policy issues (yes… Brexit), local councils are the best placed to address local policy issues such as housing, planning or mobility. The same Councils Can report goes on to argue that “Councils are in the unique position of being able to make the real and effective change needed locally that will ultimately solve some of the biggest problems the nation is facing – shaping the places we live in, improving the environment, making our communities more cohesive and changing the lives of those who live there. (…) No government will ever be able to deliver the changes needed at a local level – that is the role of councils. (…) At a time when trust in many of our institutions is diminishing, there is evidence that it is local politicians that people trust to make the right decisions for them and their families.”

As is highlighted in the report, local governments often have first hand knowledge of the issues they are trying to solve. When experimenting with new solutions, they can easily measure the results and see up close where investments can be made. More importantly, because of their closer connection to citizens, they can also rely on the collective intelligence of their communities. At a time of austerity and budget cuts, this knowledge is an invaluable resource. Continuous citizen dialogue helps councils make better decisions by ensuring that funds are spent strategically and meeting the most urgent of the community’s needs.

“Priceless local knowledge and relationships with communities and businesses has helped councils make the best use of increasingly scarce resources.”

Councils Can report, 2019

Main challenges for localism

There is an interesting paradox that lies at the heart of localism. In a sense, the push for localism is not unlike the push to leave the EU – it calls for more local prerogatives, end of centralised powers and shorter decision-making circuits. However, a recent study by Ispsos Mori has shown that the cries to “take back control” do not really translate into full-fledged support for localism: amongst Brexit voters, there was actually a low propensity to give local institutions more power over tax.

There is a similar reluctance to really embrace localism within the wider public. Whilst a majority of citizens agrees that local governments should be given more powers, only a minority is ready to accept to yield powers to local councils where it matters the most: only 40% of citizens would be in support of giving local councils more power, and only 41% are willing to devolve tax powers. So where does that leave localism?

The answer perhaps lies in an interesting number given by the Hansard study: although citizens are disillusioned with the political life, trust institutions less and say they’re less likely to engage, they’re still willing to take part in the country’s political life. “Interest in politics” and “propensity to vote” are still amongst the highest levels ever recorded. Although these numbers have slightly decreased in recent years, 41% of citizens still say they would like to be “very involved” or “fairly involved” in local politics – almost 10 points over the same results for the national level.

By encouraging citizen proposals, and going beyond simple referendums to instigate true citizen dialogue, local councils could reignite citizen involvement. Sharing information regularly, giving citizens the tools to voice their ideas and making the decision process more transparent could rebuild trust and help councils improve their service delivery. Improved efficiency would not only help reduce costs – it would also make the case for increased devolution and encourage support for localism amongst citizens.

Rather than focusing on taxation powers and increased legislative prerogatives, localism could be seen as a way to empower citizens and innovate from the ground-up. Want to get started in your local council? Give us a call!