In recent years, citizens’ assemblies, panels, and committees have increasingly been implemented at all levels of government across the globe. They’ve been particularly useful to address polarizing issues such as climate change, with the infamous Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat commissioned by French President Macron as a recent national-level example.

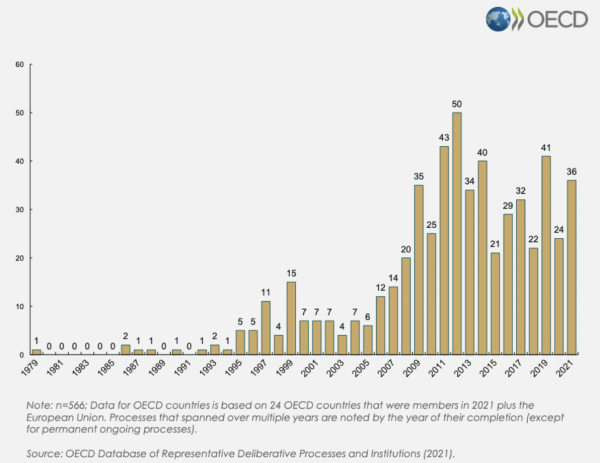

At the same time, smaller communities and municipalities have also been catching the deliberative wave. This is apparent from the latest OECD report on representative deliberative processes, which was recently presented by Claudia Chwalisz at the G1000 Autumn School on deliberative democracy.

What is deliberative democracy?

Whereas participatory democracy is more about volume, with a large number of people generally involved in the consultation process, deliberative democracy aims to bring together a smaller group of community members, representative of the total population, to find common ground on a certain issue. Although deliberative processes used to happen mostly in person, now (as of the pandemic) the process has also been implemented virtually.

There isn’t a single model for deliberative democracy. On the contrary, various conditions and criteria can shape the process and create unique models of implementation. In principle, a citizens’ assembly involves at least 100 people for a minimum of 18 weeks, while a citizens’ panel or jury generally has less than 50 people and can assemble for a shorter period of time.

Although there is no set-in-stone framework, there are some good practices and guiding principles to keep in mind.

11 good practice principles for deliberative processes

- Purpose

You need to ask the right question(s). Don’t ask “How can we solve the climate crisis?”. Instead, ask “How will we lower greenhouse gasses by 50% by 2030 in the spirit of social justice?”. This helps the discussion focus on concrete, measurable solutions instead of opening up a whole can of worms.

- Accountability

The deliberative process should generate recommendations that can be taken up at the government level and should create impact through direct influence on public decision making.

- Transparency

The details of the deliberative process should be properly communicated to the public. It’s important to give sufficient information on the process and set realistic expectations through transparent communications that are detailed enough to paint a full picture and accessible enough that anyone can find the information and process it.

- Representation

Deliberative democracy requires a group of community members – representative of the population as a whole (age, gender, education, location, socio-economic status, migration background) – to engage in the process.

- Inclusivity

You should break down the practical barriers to participation in order to allow all citizens to attend. Child-care, transportation, and an attendance stipend are all ways to ensure equity.

- Information sharing

It’s important to provide the group of participants information from a wide range of sources and experts on the issue they’re deliberating about. They should have the opportunity to ask for additional information, such as when they feel they have only heard one side of the story or when they don’t fully grasp all aspects of the problem yet.

- Group deliberation

Participants should be able to find common ground. This entails careful and active listening, weighing and considering multiple perspectives, giving every participant an opportunity to speak, using a mix of formats that alternate between small group and plenary discussions and activities, and using skilled facilitators to help keep the process on track.

- Time

For an impactful deliberative process, you need a minimum of 4 days of deliberation, though most processes are typically longer.

- Integrity

The process should be run by a coordinating team independent from the commissioning public authority. The final call on process decisions should rest with the co-ordinators rather than the commissioning authorities.

- Privacy

Participants should be protected from undesired media attention and harassment, as well as to prevent lobbyists from being able to reach participants. The identity of participants may be published when the process has ended, at the participants’ consent. All participants’ personal data should be treated in compliance with the GDPR and other international good practices. - Evaluation

Participants should anonymously evaluate the process based on objective criteria (e.g. on quantity and diversity of information provided, amount of time devoted to learning, facilitation neutrality). An internal evaluation by the coordinating team should be conducted against the above good practice principles to learn how to improve future practice. The deliberative process should also be evaluated on final outcomes and actual impact of the recommendations.

Recruiting community members for deliberative processes

To recruit community members for a deliberative process, a two-stage sortition method is usually applied.

First, a random sample of the population is drawn and in the second stage the selection by lot can be stratified based on criteria such as gender, age, location, socio-economic status, migration background, and other criteria. For residents, being asked to participate in a citizens’ assembly taps into their sense of civic duty. It’s often difficult to convince community members to join, but once in the room, people tend to want to stay. Therefore, the invitation itself, how it’s drafted and how it comes across, is of the utmost importance. It should feel like an invitation to a special occasion: both formal and friendly, elegant, and very inviting. Adding a FAQ list (e.g. about the dress code) as an addendum to the invitation can help to reassure and convince people to join.

The response rate to invitations for a citizens’ assembly or panel averages between 3-10%. Until citizens’ assemblies become more common practice, other tactics should be applied to encourage people to participate. Traditional methods such as going door-to-door can be a good strategy to raise the response rate and find out why people did not respond positively at first.

Recent deliberative case studies

- Following France’s yellow vests movement and the global youth for climate movement, President Macron initiated a great debate, and subsequently ‘le Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat’. This Citizens’ Assembly was to find common ground on measures against climate change. The deliberative process involved 150 citizens, ran for about 9 months, and in the end it delivered 149 recommendations. However, many of the recommendations got turned down in the ministries and parliament, leaving minimal room for real impact. An interesting feature to this deliberative process was the use of the reverse conference methodology: instead of listening to a classic presentation, participants asked questions to the experts who attended the event.

- In 2019 in Belgium, the German-speaking community (of 80,000 inhabitants) installed a permanent Citizens’ Council and Assembly to serve as a third democratic institution operating next to the Parliament and the Executive branch. With the aim of providing the community both a permanent voice in the decision-making process and also a systematic monitoring system to ensure their recommendations are followed up and taken into account, this Ostbelgien model is unique because it is a permanent process that consists of a 2 layered structure and is backed by regional law. The Citizens’ Council is in charge of agenda-setting, selecting participants , organizing and moderating the deliberative process, and monitoring implementation. The Citizens’ Assembly debates on the issue, consults experts, and formulates the actual recommendations. Up until now, they’ve taken up three different topics: elderly care, inclusion in education, and affordable housing – a deliberation which is taking place as we speak.

- In the German city of Werder (Havel), a deliberative process was launched to discuss issues related to the local Tree Blossom Festival and to come up with an improved concept. A group of citizens was randomly selected to share insights and bring ideas to the table. Some of the ideas would have never been taken seriously, let alone been approved by the city council, if they hadn’t been proposed by the citizens’ panel. For instance, a group of community members proposed a minimum price for the wine sold at the festival, suggesting that it would deter alcohol being the main attraction of the festival and decrease the nuisance it had been causing. .

For more case studies, consult the full OECD Database of Representative Deliberative Processes and Institutions.

5 takeaway do’s and don’ts of deliberation

- Deliberative democracy is still a field in full expansion and development. We have to learn by doing. There are currently over 20 forms of institutionalization taking place. What’s important to keep in mind is that you need a pioneer within your organization – a change-maker who has the ability to push things forward and convince others as a catalyst.

- It’s essential to create trust in the deliberative process and build trust with community members. Persuade them that their participation counts, and that recommendations made will have an actual impact at the decision-making stage. Regarding the outcome of a deliberative democracy process, in principle, the organizers have a duty to follow-up, whereas residents have a right to follow-up. Therefore, you should design the follow-up process and accountability requirements at the beginning of the deliberative process.

- Including politicians in a citizens’ assembly or panel may skew the dynamics, but it can also lead to politicians becoming ambassadors of the citizens’ recommendations, while at the same time building trust between community members and politicians. This is the general set-up for the deliberative committees of the Brussels Parliament. Members of Parliament make up a quarter of the committee, while three quarters are randomly-selected citizens. Together, the committee members propose recommendations on which the parliament must decide within a timespan of three months.

- Sharing successful results of previous deliberative processes will boost enthusiasm and willingness to participate. We’re still in the phase where the value and impact of deliberative democracy needs to be shown by example.

- Only 40% of all deliberative processes are being evaluated afterwards. However, evaluation is crucial to learning and finetuning the models that exist today. Be critical, and inquire how the process can be improved for next time.